For more than half a century, the logging industry dominated the economic and social life of the Highlands, leaving an indelible mark on the people and the land.

Pine: England’s Prize

Logging had a major impact on the early development of North America. When Britain’s traditional Baltic supplies were threatened by war and political problems, the British navy set its sights on the New World for the squared pine timbers needed for ships’ masts. White pine was prized because of its size and straight, knot-free grain, and because it can be worked easily with hand tools.

North American Expansion

Following the American Revolution, England relied on the forests of Nova Scotia, and then moved on to exploit pine reserves farther west. At the beginning of the 19th century, England was the main consumer of Canadian timber. But as American settlers pushed westward, the United States became Canada’s main trading partner for pine.

White pine was thought to be an inexhaustible resource; so no effort was made to replant what was cut. By the 1870s, the big pines were gone and the squared-timber trade was at an end. The logging industry turned to the production of lumber and sawmills sprang up throughout the province.

Haliburton: A Logger’s Paradise

The first region of Ontario to be logged was the Ottawa Valley, where as many as 25,000 men were employed in logging and related industries as early as 1806. In the late 1850s, logging companies moved into the Haliburton Highlands and found paradise.

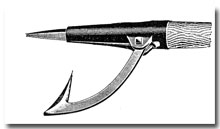

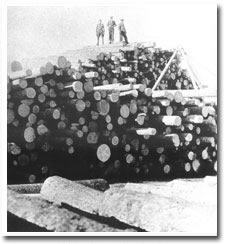

The rugged terrain was covered with massive stands of mature white pine, many trees reaching heights of 250 feet. The region also abounded in red pine, maple, hemlock, spruce, beech, oak, and birch, and yielded about one-and-a-half times that of the Ottawa Valley. Above all, there existed here a ready-made transportation system of hundreds of linked lakes that flowed south and west to lumber mills in Gravenhurst, Bracebridge, Bobcaygeon, Fenelon Falls, and even Trenton.

Size Matters

The immensity of the logging operations in this area is difficult to grasp, but records help tell the story. For example, in 1872, the Gilmour Company produced 22 million board feet of lumber in its mill at Trenton, using both Haliburton’s timber and its waterways.

Resources Depleted

In the 1890s, the timber reserves in the northern watersheds became depleted, production declined, and jobs were eliminated. An 1897 American trade tariff resulted in further job losses that had a serious impact on the economy of the Highlands and the counties to the south.

The river drives continued throughout the early 1900s, but on a much smaller scale. The industry began concentrating on sawlogs instead of massive pine timbers, supplying softwood to mills in Gooderham, Haliburton, Minden, Coboconk, Bobcaygeon, Fenelon Falls, and other smaller centres.

The End of an Era

The Gull River in Minden saw its last river drive in 1929. The log chute that was constructed as part of the Orillia Light and Power dam near Minden in 1935 was never used.

The Hawk River saw its last big drive in 1947, when the Hodgson-Jones Lumber Company ran six million board feet to Hall’s Lake. This chute was last used was in 1952.